While simultaneously trotting barefoot across a parking lot there and watching a very pretty girl, it gradually dawned on me that I had slammed a foot into a concrete divider. The doctor said it wasn't worth splinting the broken big toe, so I tried to ignore it.

The Swalker was too scruffy and slow to sell in Florida, so on July 5 Frank Bering, a hotel heir who owes me a free room in Chicago, and I "left jetties at Port Everglades at 11:30 EST", bound for New York. Nightlife to 2 AM had made us tired. The pleasant wind changed from southeast to south, so I raised the tradewind jibs even though beyond the tradewind area.

July 6: We switched back to mainsail and genoa at dawn, and went to the approximate center of the Gulf Stream, as indicated by the passage of an occasion commercial vessel, whose captain would know better than we where that is. "We're not on watches yet: one just sticks to the tiller a little longer than he can stand it, then calls on the other". We ran out of cigarettes, as both of us had planned. Skip to:

July 8: "Frank sick, loses 2-tooth plate overboard with his lunch, then is normal again. Night: Thunderstorms with lightning strikes apparently 100' from boat". Skip to:

July 10: Paraphrased from log: "Just as Frank came on deck near dawn, a bright light appeared dead ahead. We're too far offshore for that to be land. Not a ship, for no red and green lights. From whence did it come on this clear night ? In 5 minutes the mystery is solved. It is a submarine newly risen. She passes us to starboard, a green light finally showing". Skip to:

July 12: "Around 4 PM sighted several porpoises, then struck a 2" x 10" plank 12 feet long. At 5 PM sighted Virginia Beach. Frank says he is overdue and wants to get off. A launch with 4 youths comes over from the moored pilot vessel named Virginia, and offer to take Frank ashore. First they speak to the captain, who says, 'We're not running a passenger service', and threatens to report us to the Coast Guard for unspecified violations. We follow his directions to the nearest dock, but missing lights and unpredicted stakes made us suspect the captain was trying to beach us. So we returned to the ocean.

July 13: It was dangerous trying get Frank ashore. We entered Assateague Inlet, Maryland, for which I had no chart. We were briefly grounded on an incoming tide, so we headed to sea again, touching bottom a few times in surf.

July 15: "While sleeping, in the cockpit so I'd probably wake if any ships neared, I was woken by a bright Aldis lamp shining down on me. "Where are your lights ?", the voice demanded from the freighter deck above me. He was right and I wrong: I lit the lights.... I sighted whales about 8 times this day, right off New Jersey. Each had a fin relatively close to the tail, and was long. Obstacles increasing; fish stakes far at sea, missed unlit fisherman's buoy by 2 feet, wore long underwear because of the cold, variable wind sometimes dead ahead so sometimes used engine". Skip to:

July 17: "Entered New York Harbor. Much traffic, especially ferries which ignore rights of way. I was thrilled to exchange salutes with the departing Queen Mary.

The original Queen Mary salutes the Swalker in New York Harbor.

|

I tied up at a dirty dock in Brooklyn, flying the flag showing that the boat and I were American. A customs agent arrived, unnecessarily because I had come from Florida USA, and ignoring me, ordered, 'Someone find out what language this guy speaks'".

July 18: I motored up the East River, under the (click): Brooklyn Bridge ,

Going north on the East River. Brooklyn bridge ahead. Manhattan skyscrapers on the left.

|

past the United Nations complex, through the whirlpools and turbulence of Hell's Gate, to City Island, where I left the Swalker for overhaul and sale. The broker, Leo Keane, had just been ditched by his girlfriend because he was blind. Festoons of marine growth that had significantly slowed the Swalker were removed from the hull, and it was painted white, with a required new number attached.

After "Why did you do it ?", the question most asked about this trip is, "Would you do it again ?" The answer is no but I'm glad I did it. I wouldn't do so now, because I'm older and married and have other passions of the mind. The heights of euphoria I felt, the pleasure of overcoming problems, seem impossible to communicate.

Forty years later my wife Margery and I chartered a float plane to see the giant grizzly bears of the remote Katmai National Park in Alaska. We saw several very close, then helped a young man, Timothy Treadwell, pack up his summer camp surrounded by grizzly paths, load the gear into our plane, and gave him a ride back to civilization. On the way he said that although many people said his bear friends would kill him some day, it would have been worth it. I felt the same way about what I did. A few years later the remains of his partly-eaten corpse, and that of his girlfriend, were found at his camp, and the documentary Grizzly Man, about him, was widely shown. I've been a lot luckier.

The ethical basis for solo sailing has been debated at length. One side says that since proper seamanship requires that a crew member or officer be aware of the vessel and its surroundings at all times, and since it's impossible for the solo sailor to avoid sleep, then solo sailing is wrong. I believe that if the solo sailor endangers noone else, then he is acting ethically. Shortly after my ocean crossing, a blimp went to monitor a yacht in trouble off New Jersey. The sailors survived, but the blimp went down and two occupants died. I feel about that as I do about winter climbers on Mount Washington calling for help on their cell phones in hazardous conditions. That's why I had no radio transmitter on the Swalker. Otherwise I passionately support the right of anyone to take any risks, or his/her own life, if that doesn't hurt others much. So I think it wrong for a parent of young children, or a doctor with unique life-saving skills, to take extreme risks or his/her own life. Nobody needed me then, but I took reasonable precautions to minimize or avoid risks. The occasions of greatest danger, and that was usually to the boat and not me, were not in the middle of the ocean. "But such a small ship" is irrelevant: ping-pong balls are quite seaworthy.

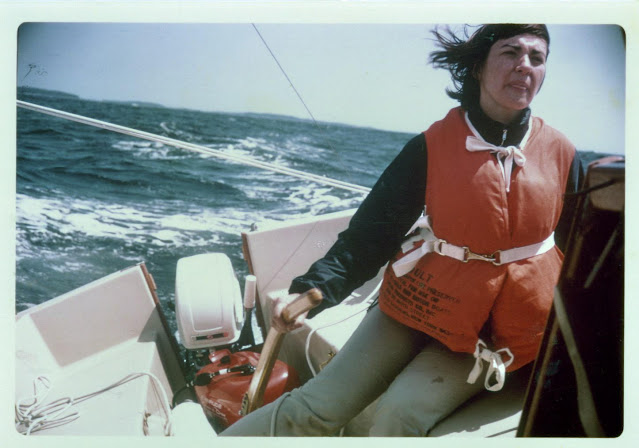

On June 14, 1968 Marge and I were married. The next day we embarked on the nautical part of our honeymoon, the first users of a Cal 25 sloop just bought by a young Hinckley, who couldn't afford one of the famous Hinckley megayachts built by his family.

Before leaving our mooring for the first time I was using the head (toilet) while Marge was on deck drying out blankets, which had wicked up moisture that condensed on the inside of the cold "Tupperware" hull. I heard a scream and stood up, dishevelled, blood coursing down my forehead from the deck support I had just crashed into on the unfamiliar boat. When I found that she had called out because she had shaken a key overboard, I said a few words about the difference between an emergency and an inconvenience. I dove a few times, but could not find the keys on the muddy bottom.

The next morning I rose to greet the dawn on the deck of our boat, anchored in tiny Duck Harbor on Isle au Haut. We were alone. The scene, with the multicolored sunrise behind me reflected on the Camden Hills on Penobscot Bay to the west, and the green spruce around us on the shore, was so achingly beautiful that I remember the lump in my throat.

We remember fondly our stay in the harbor on Matinicus Island, enforced because we woke to a fog so thick we could see its wisps around our sloop. A lobster boat came into the harbor through the fog. We talked with the one man aboard, who spoke with the distinctive accent of the island, using expressions like thick-a-fog. He invited us to supper with him and his wife and overnight at his home. There he and his wife spoke with Massachusetts accents, not the Matinicus dialect. He had been born on the island, went away to become a high school principal in Massachusetts, and took mandatory retirement because of his age. Too old for the classroom, so he was operating a boat alone daily on the wild foggy Atlantic. They offered to let us sleep on the bed and in the room used by Edna St. Vincent Millay, but we declined the honor and slept in another room.

In later years we rented (chartered, in boat language) yachts comfortably bigger than the Cal 25. We had many adventures while exploring the Maine coast, and got as far as 100 miles up the St. John River from the reversing falls at St. John, New Brunswick.

I had been indoctrinated - permanently, I thought - by the Swalker voyage, and our love of sailing grew jointly. We planned to retire on a sloop, which we meticulously detailed. It had to have a metal hull for safety, probably steel. It was to be about 36 feet long: shorter would mean more crowded, longer would mean harder to handle and over our budget. We attended several boat shows in Newport and Annapolis, and visited examples of such a vessel in Florida, Ontario, and Maine. The latter was the Kaiulani in Portland, Maine: we almost bought that absolutely perfect craft.

For decades the following was framed in my mind, from Racundra's First Cruise, by Arthur Ransome:

Before leaving our mooring for the first time I was using the head (toilet) while Marge was on deck drying out blankets, which had wicked up moisture that condensed on the inside of the cold "Tupperware" hull. I heard a scream and stood up, dishevelled, blood coursing down my forehead from the deck support I had just crashed into on the unfamiliar boat. When I found that she had called out because she had shaken a key overboard, I said a few words about the difference between an emergency and an inconvenience. I dove a few times, but could not find the keys on the muddy bottom.

The next morning I rose to greet the dawn on the deck of our boat, anchored in tiny Duck Harbor on Isle au Haut. We were alone. The scene, with the multicolored sunrise behind me reflected on the Camden Hills on Penobscot Bay to the west, and the green spruce around us on the shore, was so achingly beautiful that I remember the lump in my throat.

We remember fondly our stay in the harbor on Matinicus Island, enforced because we woke to a fog so thick we could see its wisps around our sloop. A lobster boat came into the harbor through the fog. We talked with the one man aboard, who spoke with the distinctive accent of the island, using expressions like thick-a-fog. He invited us to supper with him and his wife and overnight at his home. There he and his wife spoke with Massachusetts accents, not the Matinicus dialect. He had been born on the island, went away to become a high school principal in Massachusetts, and took mandatory retirement because of his age. Too old for the classroom, so he was operating a boat alone daily on the wild foggy Atlantic. They offered to let us sleep on the bed and in the room used by Edna St. Vincent Millay, but we declined the honor and slept in another room.

In later years we rented (chartered, in boat language) yachts comfortably bigger than the Cal 25. We had many adventures while exploring the Maine coast, and got as far as 100 miles up the St. John River from the reversing falls at St. John, New Brunswick.

I had been indoctrinated - permanently, I thought - by the Swalker voyage, and our love of sailing grew jointly. We planned to retire on a sloop, which we meticulously detailed. It had to have a metal hull for safety, probably steel. It was to be about 36 feet long: shorter would mean more crowded, longer would mean harder to handle and over our budget. We attended several boat shows in Newport and Annapolis, and visited examples of such a vessel in Florida, Ontario, and Maine. The latter was the Kaiulani in Portland, Maine: we almost bought that absolutely perfect craft.

For decades the following was framed in my mind, from Racundra's First Cruise, by Arthur Ransome:

"Houses are but badly built boats so firmly aground that you cannot think of moving them. They are definitely inferior things, belonging to the vegetable not the animal world, rooted and stationary, incapable of gay transition... The desire to build a house is the tired wish of a man content thenceforward with a single anchorage. The desire to build a boat is the desire of youth, unwilling yet to accept the idea of a final resting place... When it comes, the desire to build a boat is one of those that cannot be resisted. It begins as a little cloud on a serene horizon. It ends by covering the whole sky, so that you can think of nothing else. You must build to regain your freedom".

Precisely so.

But we still had jobs, we were getting older, Marge's mother needed increasing TLC, and our love of the water came to be overshadowed by our love of the land: the Maine woods, Alaska, Argentina, Norway, and most of the places in between. Abandoning our intention to cruise Atlantic shores from Maine to Florida to Bermuda to Norway was difficult, and took about a year to accept. We are left with no regrets, and the intention to visit many more anchorages, coastal and inland, than we could afloat.

But we still had jobs, we were getting older, Marge's mother needed increasing TLC, and our love of the water came to be overshadowed by our love of the land: the Maine woods, Alaska, Argentina, Norway, and most of the places in between. Abandoning our intention to cruise Atlantic shores from Maine to Florida to Bermuda to Norway was difficult, and took about a year to accept. We are left with no regrets, and the intention to visit many more anchorages, coastal and inland, than we could afloat.

On our 1968 honeymoon in our rented sloop, about 10 miles off the mid-Maine coast.

Interesting stuff. I had remarkably similar experiences in 1956 and 1957, including the Saone and Rhone River descents and the Atlantic Ocean crossing. It would be fun to compare notes.

ReplyDeleteEd Karkow

34 Indian Point

Waldoboro, ME 04572

207 832-6934

karkow@midcoast.com

I so love your blogs thank you

ReplyDeleteMichelle